It’s still on my bookshelf: the paperback copy of Moby Dick (Signet Classic, 75¢) that I read while serving in the Army in Vietnam, indelibly stained with the red dirt from western edge of III Corps, along the Cambodian border, where I spent six months in the late 1960s. It is about the same latitude as Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, and a tourist destination for many Americans.

I was a young man with liberal beliefs who went to a Quaker college. How did I end up in the Army, fighting in a war I despised?

I graduated from college at the height of the war, in 1967, and enlisted in the Army that fall. Even after more than twenty years of being alive, living in a loving and supportive family and during which I received a great education, I still didn’t know my own mind—or was too unsure of myself to act on what I believed. I had convictions, but not the certainty or courage of them. I didn’t understand at the time just how terribly wrong that war was, how criminal, how senseless.

I certainly wasn’t in favor of the war, but apparently I wasn’t against it enough to convince myself to seek status as a conscientious objector. Nor was I ready to go to jail for refusing to go, or ready to abandon this country for Canada or elsewhere. There was still a draft and not yet a lottery, which held out the promise of a number high enough to make getting drafted unlikely.

I loved languages and had heard about Army language school; it had a very good reputation and was in Monterey, CA. That seemed attractive, and I thought it might help me avoid combat, although there were no guarantees of getting a particular training or assignment, whether you were drafted for two years or enlisted for three.

I decided to enlist. It seemed the best way to avoid going to Vietnam

In spite of that utter uncertainty, I decided to enlist. It seemed the best way to avoid going to Vietnam, which I realize makes no sense. My girlfriend’s father tried to talk me out of it. Just get drafted, he told me, but I don’t recall having a really serious conversation with him or anyone else. I remember realizing the magnitude of my mistake on the train from Philadelphia down to basic training at Ft. Bragg, NC. My god, three fucking years! How am I going to survive?

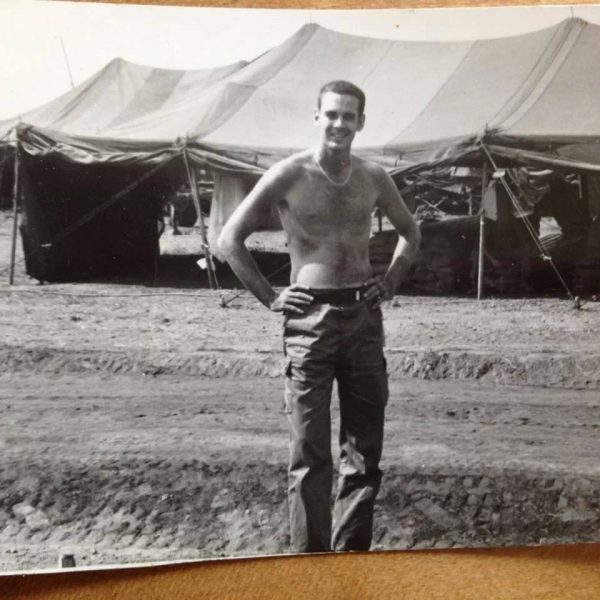

I did well in basic training, because I pretty much always try to do my best, at whatever, and I did what they wanted. I wanted to survive. I guess I decided to make the best of it—not a bad survival skill. Physically, Basic wasn’t as hard as I’d thought it would be. Mentally, however, it was one of the hardest things I’ve ever been through, maybe the hardest. As best I could, I shut down my emotions and concentrated on surviving, on coming out reasonably whole at the end. I found out that I could survive, even while feeling helpless, utterly alone, in a situation from which I could not extricate myself – at least not without dire consequences. One of the two drill sergeants who rode herd over us—and whose face I can still remember—said I was the best Jew he’d ever had; I didn’t try to get out of stuff for religious holidays. Check one for the chosen people.

There were no guaranteed assignments at the time, even for enlistees, and the Army has its own logic. So I didn’t get assigned to language school, but rather to Army Intelligence School in Baltimore. All of our training was geared around the concept of the Cold War in a European setting, in spite of the fact that Vietnam was a guerilla war, not a “conventional” war. Not fair, you Vietnamese, with your tunnels, punji stakes, and sandals ingeniously made from discarded American tubes and tires! Play by the rules! I remember thinking that, like the colonists during the Revolutionary War, the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese used unconventional tactics against an invader who didn’t know the territory, or understand or respect the history and culture of the place. Home court advantage is real.

After intelligence school I was sent to Okinawa, where we had several bases and lots of planes, including the B-52s whose bombing missions left much of Vietnam badly pockmarked with craters, which in the western part of the country provided a convenient way to demarcate Vietnam’s borders with Cambodia and Laos.

I didn’t really have to go to Vietnam at all; I could have ridden out the war in Okinawa, doing nothing—busy work, pencil-pushing, truck-cleaning, picking up cigarette butts. But our unit, an intelligence detachment within the 1st Special Forces Group (Green Berets), regularly sent people to Vietnam for a 6-month temporary duty (TDY) to work in a “special operations group” within the 5th Special Forces Group stationed in Vietnam. I decided to go. If I was guilty of something just by being in the military during this war, I thought I should at least go see it for myself, though looking back now, I realize what terrible anguish that decision must have caused my family.

I knew that I’d be in Vietnam for a limited time, about half the normal 13-month tour, and that I wouldn’t be a grunt, directly involved in combat, out in the field traipsing through rice paddies, “humping the boonies” as it was called. I’d be in a base camp somewhere, debriefing returning recon teams (RTs) who’d been out in the field trying to recon the terrain and try to see what the enemy was doing.

I’m not sure when I found out that the RTs were doing highly-classified, illegal cross-border operations, all along with borders with Cambodia and Laos, something called Operation Daniel Boone. Inserted about five klicks (kilometers) over the border, delineated by a line of bomb craters, teams of two Americans and 3 Montagnards (“Yards”) or Cambodians were there not to engage the enemy but rather to observe and report back on what they’d seen of the terrain, enemy activity, and anything else of interest. It was my job to debrief them and write a report. All this took place not long before the U.S. invaded Cambodia. The intelligence that was gathered by the RTs might have laid the groundwork. In fact, that’s quite possible, if not likely.

Not long before Nixon ordered an invasion of Cambodia—a nominally neutral country—the Army sent in not a recon team but a much larger unit that included people from the Special Forces unit that I was with. I remember that lots of people didn’t want to go, because of where they were being sent. I think it was called the Fishhook, thought to have lots of VC and NVA. Sure enough, the force made contact immediately after being inserted by helicopters (not exactly the quietest things) and got the shit kicked out of them. There were lots of casualties. I know about this, because I was flying over the area while this was going on as a passenger in a 2-seater radio-relay plane, which was there to enable the ground troops to talk to command people. I could hear the bad shit even though I couldn’t see it. When it was over and we landed, I was supposed to debrief people and find out what had happened, but I found myself too shaken to do so. In recently looking for information about Quan Loi, one of the places I’d been stationed while “in country,” I ran across — for the first time – a link where this debacle is discussed.

If my war is Vietnam, my drug is (obviously) grass. I smoked a little in college, and the dope on Okinawa was stronger, better and cheaper, even at $5.00 for a small matchbox, the kind that holds two-inch wooden sticks. I shared some dope one night with a friend, who apparently ratted me out to the company executive officer (XO). A few days later, the XO told me that I needed to open my locker so it could be searched. He found the matchbox and a few small leaves of grass—a smaller amount than the salt you’d put on an order of breakfast eggs. But it was enough to cook my goose; the Army sent me—without orders—from the intelligence detachment to a signal company, also within the 1st Special Forces Group, that very same day and later stripped me of my top-secret security clearance.

No one at my new assignment knew why I was there except for the company commander and First Sergeant, and apparently they didn’t really care as long as I went along and got along, which I was happy to do. The company was located on the top of a hill, from which there was a beautiful view of the Pacific. I even got to play on the company basketball team. I kept my sergeant’s rank (E-5) and eventually got to move out of the barracks into my own room, since I was a non-commissioned officer. Lots more people in my new company smoked dope, too, although I found out later that they were worried about my being a narc, since I’d shown up mysteriously, without written orders.

In a strange kind of way, my experience in ‘Nam was the best, or least bad, of all my time in the Army. The object was to do my limited job and stay sane and alive. And I learned that there were some smart, decent people in the military. Hate the war, not the soldiers.

All the same, I really didn’t like myself. I was a cog in a stupid, destructive, evil enterprise. I kept my head on straight by thinking that the whole country shared my guilt, that it was collective and national, not just individual. I don’t know if that’s true but it has helped me to live with, and eventually make peace with, myself. Still, I wondered what in god’s name I would tell my future kids about what I’d done, and whether the deep shame that I felt would persist and be overwhelming.

Being in the Army in general, and my experience with the search of my locker in particular, made me keenly aware of what rights I did or did not have—in both a practical and theoretical sense. I never wanted to wonder about my rights again, and I wanted to help other people know theirs, so I decided to go to law school. I was still totally clueless about how to find a career and job, but I applied to a bunch of top schools and one state school in Colorado, where my brother was living. I took the LSAT in a Quonset hut on Okinawa and did well enough to get into just one—CU-Boulder, which was affordable at the time and, while not in the top tier of schools, at least a respectable institution.

After finishing law school and passing the bar, I scoured the country and ended up with a legal aid program in Gettysburg, Pa., where I found a job, and then a spouse and family. I managed to make a good and fulfilling life, both personally and professionally. So my military service did have some value; in a somewhat convoluted way, it resulted in a meaningful and satisfying 40+ year career representing lower-income people in civil cases. I’m a bit surprised, but very happy and proud, that both of our kids are legal aid attorneys, too, working to maintain and advance the rule of law.

And despite my anxiety over having fought in Vietnam, I am amazed and relieved to find that no one has treated me like a bad person, much less a war criminal, at any time—not during my service, upon my return, or since then. Far from it. My friends have always been understanding. And now, I get to stand up with other veterans when called out for praise in a public arena, as happened during a recent visit to the Grand Ole Opry in Nashville.

I feel immune from almost all criticism if I publicly disagree with something the government has done or the position some politician has taken. I generally seek compromise and understanding. I still feel unsettled about my experience, even as I write this fifty years later, but now at least I feel comfortable about expressing and fighting for my core beliefs, about which I am, finally, very sure.