In 1966 “The Ballad of the Green Beret” by Barry Sadler was Billboard’s Top Song. It was bigger than any Beatles, Beach Boys, Rolling Stones, or Simon and Garfunkel song. Anyone living in the era can recognize the song.

The song hit home with my high school class, and the adults in Morenci, Arizona. Our fathers had been in the military in World War II and most families had a photo of an uncle killed in the war. After high school graduation a few had a chance to go to college, others could try to get on with Phelps Dodge in the mine. Morenci life revolved around the copper mine. The work schedule was 26 days on and 2 days off. Good money, steady work. Copper was in big demand, the war needed a lot of bullets, and other things made with the metal. There was a new opportunity to get out of town and see the world.

Fighting soldiers from the sky

Fearless men who jump and die

Men who mean just what they say

The brave men of the Green Beret

Silver wings upon their chest

These are men, America’s best

One hundred men we’ll test today

But only three win the Green Beret

Trained to live, off nature’s land

Trained in combat, hand to hand

Men who fight by night and day

Courage deep, from the Green Beret

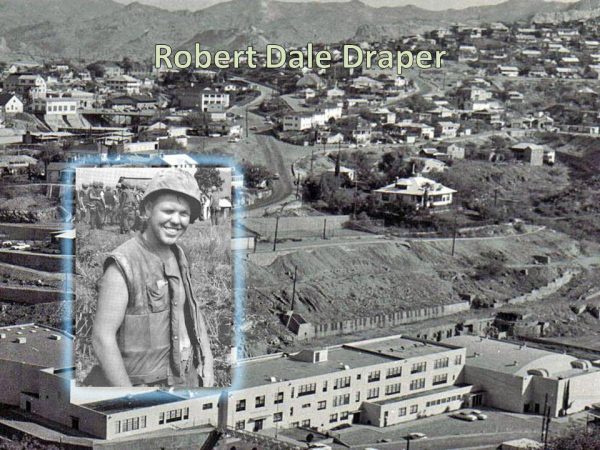

Word spread that eight of the class of ’66 along with one ’65 graduate had decided to join the Marines. Bobby Draper, Stan King, Van Whitmer, Larry West, Jose Moncayo, Clive Garcia, Leroy Cisneros, Mike Cranford, and Joe Sorrelman all went down together and signed up on the 4th of July 1966. That was one-sixth of the males in the class of 1966. A good cross section of the town. Catholics with Mexican roots, Mormons, Southern Baptists tracing back to Appalachia via Oklahoma, and a Navajo just like a WWII war movie.

A view of Morenci, Arizona

Bobby Draper, the all state linebacker was thought to be invulnerable. It was considered a rough mining town, but nobody would think of messing with Bobby. It would have been impossible to pick a fight with him because you would have to be crazy to try and he was too decent a guy to fight idiots.

The first causality in 1967 was Bobby Draper.

With that the invulnerability of youth went away.

Next was Stan King. My step mother, a fourth grade teacher told this story:

Lunch was a noisy period when school, released from the enforced quiet of the classroom got to eat, and interact with their classmates causally watched over by adults. Food was obtained from lunch boxes or the cafeteria lines, companions were located, seats taken and the cacophony of youngsters filled the room. A wave of silence caused the adults in the room to look with concern at the children, then follow the gaze of the children to door.

Suddenly all heads jerked around when inside the hitherto invisible lunch lady, Penny King, all the pain of childbirth, every drop of milk suckled from her breast, the giggles of a toddler and her dreams of grandchildren vaporized inside her and forced out that great cross cultural mother’s scream of loss heard throughout the entire wing of the school. The two Marines in dress blues had located the person they had come to see.

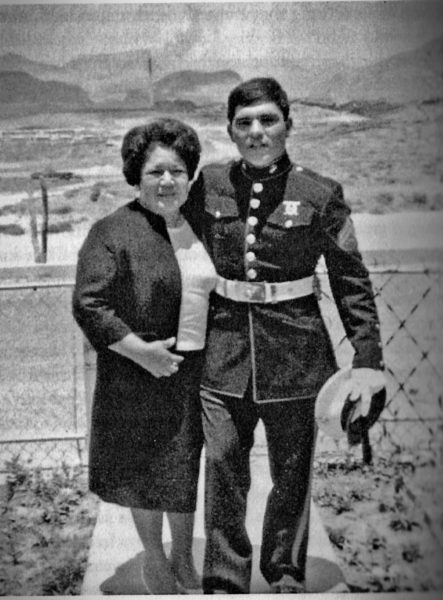

Clive Garcia with his mother

In 1968 it became a mind numbing routine. Van Whitmer, Larry West, then Jose Moncayo. All sent back and laid to rest.

The next year only four of the nine were left.

Clive Garcia loved the Corps. He took advanced ranger training and was determined to do his part in the war. He told his brother “I must do my part or I just as well as spit on their graves” [The Morenci Marines – Kyle Longley]. Joe Sorrelman who had survived a tour and Leroy Cisneros who had 13 months in country with 40 missions as a point man for the First Reconnaissance Battalion tried to tell Clive that there was no glory in combat and he would do his family a favor by not asking for a tour. Clive still felt he had to go.

On Thanksgiving eve 1969, Clive was on point when he was killed trying to disarm a 105mm artillery shell booby trap. As he was being brought home someone in the media calculated that Morenci had had the highest per capita death rate in the war. Television and print reporters descended on the town which did not desire the attention. There is no good answer to “How do you feel about your son’s death?”

Tears came to my eyes when I heard Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Big Time in The Jungle.” It is a eulogy for my classmates.

Down in Eutaw, Alabama in 1965

A young man ’bout 21, no different than you or I

He’s catchin’ catfish, and gettin’ drunk

But Uncle Sam called, he called him up

Sent him out to Vietnam

That young man

Got his life turned upside down

Turned his smile into a frown

Robbed that king of his crown

For an ideal he didn’t even know about

I got nothin’ left in the States for me

I wanna see the world you see

I know that Uncle Sam needs me

To fight for an ideal I know nothing about

Oh the drop point was dusty and the drill sergeant was loud

And he could not see the corpses for the ragin’ dust cloud

Grab your duffle bags, head to the checkpoint

Welcome to Vietnam, boys, you’re in for a hell of a fight

Take it from the ones who know

The army moves slow

Hurry up and wait, don’t sleep late

And learn to hate your brother

Before you hate your foe

On patrol out in the rice fields, them choppers flew low

Glancing for the hand signal to tell you where to go

Then the bombs started fallin’

And they pounded his brain

And he thought about Eutaw and who was to blame

For sendin’ him to Vietnam

While they were fighting and the Navy Depot in Mechanicsburg was issuing a contract for 8” shells for the USS Newport News using up Morenci copper. The Bermite Powder Company made most of the projectiles correctly and with negligent military inspection.

When my college deferments ran out and I pulled a low draft number I decided to enlist in the Navy. On April 13, 1972, fresh out of Radar A School I went to sea for the first time. The USS Newport News (CA-148) was leaving for Vietnam in such a hurry that ammunition was being loaded dockside instead of at the ammo anchorage. The band on the pier played Lynn Anderson’s hit “(I never promised you a) Rose Garden” as the ship got underway.

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

Along with the sunshine

There’s gotta be a little rain some time

When you take you gotta give so live and let live

Or let go oh-whoa-whoa-whoa

I beg your pardon

I never promised you a rose garden

Never forgave them for that.

I had thought they would never send the Atlantic Fleet flagship to WestPac. Now we were in Haiphong Harbor with artillery shells coming in. I had not understood that the USS Newport News had the largest guns afloat. It had the largest automatic guns ever made. Each of the nine barrels could fire ten rounds a minute. It could put 90 rounds in the air before the first one hit if firing at maximum range. American ground troops had mostly been withdrawn and President Nixon was relying on Naval guns and air power. More 5 inch and larger naval ammunition was fired at Vietnam than all of the large caliber shells fire by the US in WWII.

The raid on Haiphong was touted as the first multi-cruiser strike by the US in 27 years. For the next few months the routine was days off the DMZ providing gunfire support with occasional night raids against targets in North Vietnam. Workdays were twelve to sixteen hour shifts of watches, shelling, work details, punctuated with night time raids against targets in the North. Once a month there were a few days in Subic Bay, Philippines for R&R and resupply.

In addition to radar watches our section assisted at sea rearming of Turret 2. This was a tense complex operation with two ships matching speed 30 to 40 feet apart, transferring tons of explosive brass cartridges and projectiles on lines strung between the ships, pallets being moved on the deck and powders passed up and shells hoisted up to the turrets.

One evening after the ship had dropped the lines to the ammo ship we had a bit of slack time. While down on the deck we broke down the pallets to pass up the remaining 8” ammo. It was a lovely sunset, comfortable weather with a zephyr coming across the bow and calm seas. On the way the crew of radar men and gunners broke into song. With youthful bravado and irony we sang Country Joe and the Fishes “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die Rag.” Some of the verses were a little weak, but everyone lustily sang the chorus.

Well, come on all of you, big strong men,

Uncle Sam needs your help again.

He’s got himself in a terrible jam

Way down yonder in Vietnam

So put down your books and pick up a gun,

We’re gonna have a whole lotta fun.

And it’s one, two, three,

What are we fighting for?

Don’t ask me, I don’t give a damn,

Next stop is Vietnam;

And it’s five, six, seven,

Open up the pearly gates,

Well there ain’t no time to wonder why,

Whoopee! We’re all gonna die.

Well, come on generals, let’s move fast;

Your big chance has come at last.

Now you can go out and get those reds

‘Cause the only good commie is the one that’s dead

And you know that peace can only be won

When we’ve blown ’em all to kingdom come.

Seemed like a good way to release tension before General Quarters were sounded before another night raid against North Vietnam, but we were singing directly underneath the bridge. Down on the deck a sailor yelled up, “The captain says to quit singing that song!” We did.

For the men of Turret 2 it was less of dark humor and more of a prophecy.

While taking on ammo on 4th of July work halted suddenly. Down at the front turret, Storekeeper Stephen Brumfield had backed up his forklift into the lowered barrel fracturing his skull. Our first casualty.

On August 27th, the Newport News was sent on another raid against recently mined Haiphong Harbor, the most heavily defended point in North Vietnam, against the advice of the Seventh Fleet. It was hundreds of miles away from any possible reinforcement, and while the coastal batteries were not especially accurate, any lucky hit disabling the ship would have left it helpless. After the main firing run with two of the four ships already departed, four torpedoes appeared. They were approaching from dead ahead at high speed and our guns remained silent because they had a safety (?) switch install to prevent them from hitting the communications mast which had been installed on the bow. The course was altered to unmask the guns and three of the four boats were sunk by naval gunfire and aircraft. The “Battle of Haiphong Harbor” was the last time a big gun ship of the United State fought enemy surface vessels.

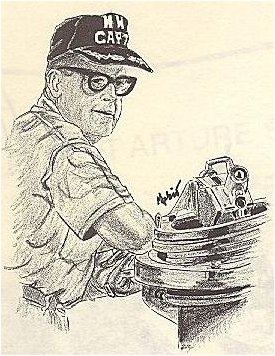

CLICK HERE to hear Captain Zartman’s after action address to the crew of the USS Newport News.

CLICK HERE to hear a recording of the gunners’ sound circuit from the USS Newport News.

Audio is from the website http://www.unm.edu/~spardo/haiphong.htm

On September 10th, James Sansone fell overboard. His body was never recovered.

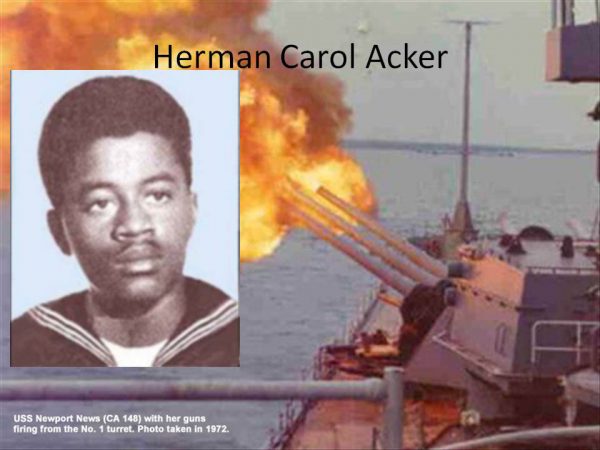

We were back at the DMZ doing routine H&I (Harassment and Interdiction) firing. As I was reporting for a midnight watch, Turret 2 fired which by now was a normal background sound which could be ignored. It was immediately followed a quieter but disturbing shudder. A projectile had exploded prematurely in the center gun, rupturing the barrel, blowing through the breech block and setting the powders in the ammo hoisting on fire. The men in booth were killed instantly, the lower decks were engulfed in flames, poisonous gases. It is possible some drowned when the sea cocks were opened to flood the turret. There were twenty dead and 36 injured.

Here’s one sailor’s description of the morning after:

“But the time came to bring out the dead. Army blankets were brought to the front. Some of the men went in and began to carry the bodies to the door where others outside helped to place them on the blankets. Each of the bodies was then handed down the line to the main deck. As one of the men attempted to take hold of a dead sailor’s arm, the skin peeled back. I had lost all emotion at that time, and as I saw the dead sailor’s pinkish, whitish flesh, I also saw his disfigured face, but I recognized him. He was a black sailor that I had seen often in the mess hall. And I thought to myself, black and white men are all the same color under the skin. As another body was being carried out, one of the carriers dropped him on one side and a gasp went out from us, and the Chief said, “Don’t worry, you can’t hurt him anymore.” Strange, but that had a reassuring effect on me, as I had never before had to deal with death so closely. I suppose that at that time, I could have pulled myself out of the line and gone to sit somewhere in the fantail where there was more fresh and clean air to breathe.

One by one, the bodies were taken to a makeshift morgue to be identified and pronounced dead. I came to realize that what I smelled that night was burned flesh. The taste stayed in my mouth for many months and several years after. And even now, in my mind, I can still see and hear and feel and smell and taste that night, October 1, 1972.”

Phil Ochs’ “Men Behind the Guns” serves me as a tribute to these men.

Let’s drink a toast to the admiral

And here’s to the captain bold

And glory more for the commodore

When the deeds of might are told

They stand to the deck with the battle’s wreck

When the great shells roar and pound

And never they fear when the foe is near

To lay their orders down

But off with your hats and three times three

For every sailor’s son

For the men below who fight the foe

The men behind the guns

Oh, the men behind the guns

Their hearts a-pounding heavy

When they swing to port once more

With never enough of the greenback stuff

They start for the leave ashore

And you’d think perhaps the blue-blouse chaps

Had better clothes to wear

For the uniforms of officers

Could hardly be compared

Warriors bold with straps of gold

That dazzle like the sun

Outshine the common sailor boys

The lads who serve the guns

Oh, the men behind the guns

But say not a word till the shot is heard

That tells the fight is on

And the angry sound of another round

Says there must be gone

Over the deep and the deadly sweep

Oh, the fire and the bursting shell

Where the very air is a mad despair

The throes of a living hell

But down and deep in a mighty ship

Unseen by the midday sun

Oh, you’ll find the boys who make the noise

The lads who serve the guns

Oh, the men behind the guns

And well, they know the cyclone blow

Loose from the cannon’s steel

And they know the hull of the enemy ship

Will quiver with the peal

And the decks will rock with the lightning shock

And shake with the great recoil

While the sea grows red with the blood of the dead

And swallows up her spoil

But not until the final ship

Has made her final run

Can we give their rest to the very best:

The lads who serve the guns

Oh, the men behind the guns

It was later determined that some of the projectiles had been sent from the factory fully armed. This information was not declassified for more than a decade.

The turret was sealed and the ship returned to Vietnamese waters. We were told we had to “Ride the horse that threw you.” I understood riding after getting thrown, however I had my doubts about riding something after it already had killed twenty men.

We did that turn on the gun line, received a farewell message thanking the ship for its service in Southeast Asia and were told we would return to Norfolk. As we were pulling into Subic Bay the ship was ordered to return to Vietnam. It had been extended indefinitely in theater. Another round on the line, then a couple of days in Subic. Now it was December and it was apparent we could not be home in 1972 if the ship was ordered back to Vietnam.

Orders were given to return to the Gulf of Tonkin. The ship set sail at flank speed due west. A significant number of sailors had failed to return to the ship and those who had returned were disgruntled. Facing what was in effect a mutiny, the ship turned around and headed toward Norfolk under radio silence. On a foggy Christmas Eve, the Newport News pulled into Norfolk. The crew was instructed not to talk to the reporters who came aboard, those who had family nearby left the ship. After everyone was gone, I went onto the base, sat down on some concrete steps to listen to sound of engines not running and feel a surface that did not roll in the waves.

Shipmates killed October 1, 1972: Herman Acker, Jack Bergman, William Clark, Charles Clinard, Ronald Daley, Raymond Davis, Terry Deal, Joseph Grisafi, William Harrison, Tommy Hawker, Robert Kikkert, Edward McEleney, Robert Moore, Stanley Pilot, Ralph Robinson, Wesley Rose, Richy Rucker, Jeffery Scheller, David Scott, and Richard Tessman.