My early years were spent on military installations from 1957 to October 31, 1967. Early 1965 we were living in Germany when my father got his orders to deploy to Vietnam. We came back to the States while my Father was deployed.

I remember attending my first public school in rural Pennsylvania. It was a cultural change to live one’s’ life on a military installation to becoming a civilian. The first big change for me was not living in a compound surrounded by high chain link fence. Every day as I walked to school I no longer walked by the Military Police who carried rifles. I realized the children I attended school with had both parents living under the same roof. The children knew their father would return home every night from work unharmed and alive.

From the age of 8 years old I realized that my father was a Green Beret Screaming Eagle, who carried a machine gun and protected the United States of America. It was difficult to explain to children that my father was in Vietnam fighting a war and there was a possibility that he could die. The other children in second grade didn’t understand what it meant to go to war or die for your county. As a military brat, I played army with my buddies and we acted out war scenes. I knew what went into the ammo box, I knew about grenades and machine guns. I knew about landmines and soldiers being blown up by landmines. I had some understanding of dying for your country.

I heard the choppers landing one by one I would see the medics bring wounded soldiers into the ER.

I received many letters from my father while he was in Vietnam. He wrote about the loss of young soldiers who were the same age as my older brother. My father made no promises that he would return from Vietnam. In the spring of 1966 my Father came back to the States on medical leave. My family once again packed our personal belonging and headed to the next military installation.

On October 31, 1967, my father retired from the military at Fort Bragg. I thought we were leaving the military life behind and becoming civilians.

I was born a sickly child and spent much time visiting military hospitals. When we came to Pennsylvania my family doctor would become Valley Forge Military Hospital. In the late 1960’s into early 1970’s Valley Forge (Military) General Hospital became a hub for soldiers coming back from Vietnam.

Being sickly, it was my father’s responsibility to transport me to and from Valley Forge General Hospital for my routine doctor visits. Although my father retired from military service you can’t take the military out of a person. I knew my father often thought about the young men who had served with him in Vietnam.

When my appointment was over my father insisted I walk with him through the wards greeting soldiers and thanking them for serving our county. I was about 12 years old when my father decided that every time we visited Valley Forge Hospital we would take a walk through the wards.

I dreaded being sick and my appointments at Valley Forge General Hospital. The smell of the wards and the soldiers moaning and groaning in pain upset me to my core. I found it difficult to look at soldiers who had no arms or legs blown off. Often while sitting in the waiting room I would hear helicopters landing. I often saw soldiers being wheeled into an open ER room. One day while waiting to see my doctor I asked my father if I was old enough to see the doctor on my own while he walked through the wards looking for soldiers he knew. My father agreed to letting me sit in the waiting room and see the doctor on my own.

Shortly after my father left the waiting room I heard my name being called and I got up and proceeded to the next waiting area located outside the ER rooms. While I sat, and waited, I heard the choppers landing one by one I would see the medics bring wounded soldiers into the ER. As I waited for my doctor I saw people coming and going from ER to ER. Oh, no; I heard another chopper coming in and within minutes the medic wheeled in another wounded soldier. All the ER rooms were occupied and there were no rooms available for the incoming wounded. The young wounded soldier was left on the gurney directly in front of where I had been sitting. The gurney was occupying the space in front of me and I had nowhere to look accept at this young man laying there screaming and crying while he thrashed in pain. I tried to focus on looking at his face and not the body thrashing in front of me. He was a young man not much older than myself. As the wounded soldier screamed in pain his sheets were being tossed about. I could see that his legs had been blown off and his abdomen was open with organs in a wire basket.

At this point I was so upset and feeling helpless while he screamed with pain, that I got up and stood at his face and said let me get you some help. I looked up and down the hallway to call out for anyone to come and help. At that moment, my doctor appears and says it’s your turn. I looked at my doctor and said please help this soldier, I can wait. Dr. Yohon looked at me and said he will be taken care of soon, I begged the doctor to treat the young soldier before me. My doctor explained that he needed to be seen in the ER room and they were all filled. I looked back at the soldier as I walked into the examination room and said out loud “I’m sorry I couldn’t help you.”

“I’m sorry I couldn’t help you.”

After my appointment, I came out in the hallway looking for the soldier who needed immediate medical care. As I peaked in the ER room I saw the young soldier quietly lying there being treated. I sat in the waiting room until my father arrived, while I sat I thought about the young wounded soldier and the injuries I had seen. This experience was much worse than walking through the wards being forced to greet and thank soldiers for their service. For the next 27 years, I would have recurring dreams where I was stuck in the stairwell of a military hospital. If I opened the door to exit, the stairwell I would be on a smelly ward with soldiers who were crying and moaning as they laid in their beds with blown up bodies.

In the reoccurring dream, there was no door I could open that did not open into a smelly ward. In my dream, I didn’t want to look at blown up bodies nor did I want to smell the wasting of flesh. The dream always ended the same way, with me sitting on a step in the stairwell trying to find a way out without encountering anyone blown up. In my dreams, I would try and think of ways to open the door and move through the ward without looking and acknowledging any wounded soldiers.

As I went through life I never told anyone of the recurring dream. In my twenties, I realized that my uncle had what they called night terrors. My uncle was deployed to Vietnam a few months after my father deployed to Vietnam. My brother had been drafted during the same war but was granted a deployment to Germany instead of Vietnam. In high school, I had a boyfriend whose number came up in the draft. I watched many people around me either deploy or be drafted into war.

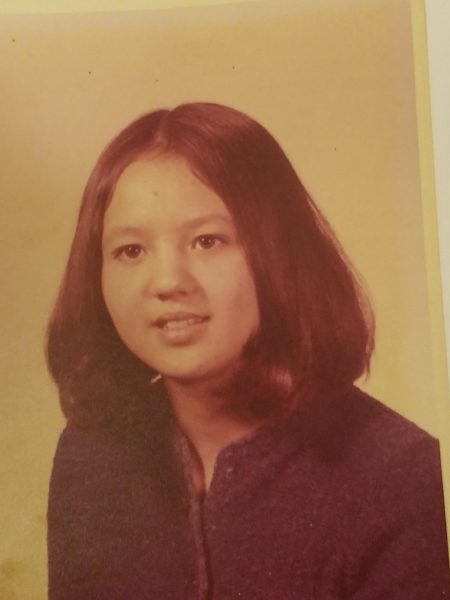

In the mid 70’s as soldiers came back from Vietnam I watched as people treated our soldiers as if they were criminals. Everyone around me in civilian life had no idea what war was about or how it affected soldiers or the causality of war. I felt as if no one understood what I had seen or how war personally affected my life. No one understood about previous wars and the outcome of war on a military family. It was difficult enough being born Amerasian, the outcome of the Korean war.

My cousin Mitsuhiko worked for the Associated Press in Japan and had just taken a transfer to the New York office. Mitsuhiko came to Berks County to visit my family and spend some time seeing Amish country. One day as Mitsuhiko was taking a walk a man confronted him and asked if he was Vietnamese. Mitsuhiko loved John Wayne so he practiced the English language by using John Wayne’s accent. In this deep Texan voice Mitsuhiko answered the man by saying he was not Vietnamese but Japanese. The older man said oh okay you must be related to the Japanese women in town. Mitsuhiko came home and told us of his encounter and being asked about being Vietnamese. I knew there would be more encounters with people thinking we were Vietnamese. I never understood when my father left military life why American people especially children were so cruel and called me all type of names. I never expected to start a new school and have children make fun of me. I couldn’t understand what was so different about me that people were mean and acted as if I had leprosy. I had several encounters with people who thought I might be a refuge from Vietnam and I proudly stood up and stated I’m Japanese not Vietnamese.

After 27 year, of dreams of being stuck in the stairwell of a military hospital I decided the dreams needed to stop. Every night before falling asleep I told myself I was no longer going to be stuck in the hospital stairwell. Eventually I had the recurring dream, this time I was determined to escape the stairwell. In my dream, I decided that I would exit the door on the lowest level of the hospital. I told myself to walk as fast as I possible could to the main corridor that led outside the hospital. I knew that I would encounter soldiers who needed medical attention and those who would be crying in pain. My plan was to stop and help anyone who called out to me and get to the main corridor as fast as possible. By planning to help anyone who cried out to me and walk as fast as possible to the main exit I never had the dream again.

Being 13 years old and helpless to render assistance to the younger wounded soldier left me with PTSD. The feeling of helpless and not being in control of the situation changed my life forever.

I went on to train and work in every unit of a hospital including the morgue. I worked with terminally dying patients who chose to dye at home. Throughout life I volunteered my time to many organizations to help those in need. I’ve taken various emergency trainings to assist on the local, state and federal level. I am thankful to live in the United States of America and to be blessed with freedom.

Janice Kille