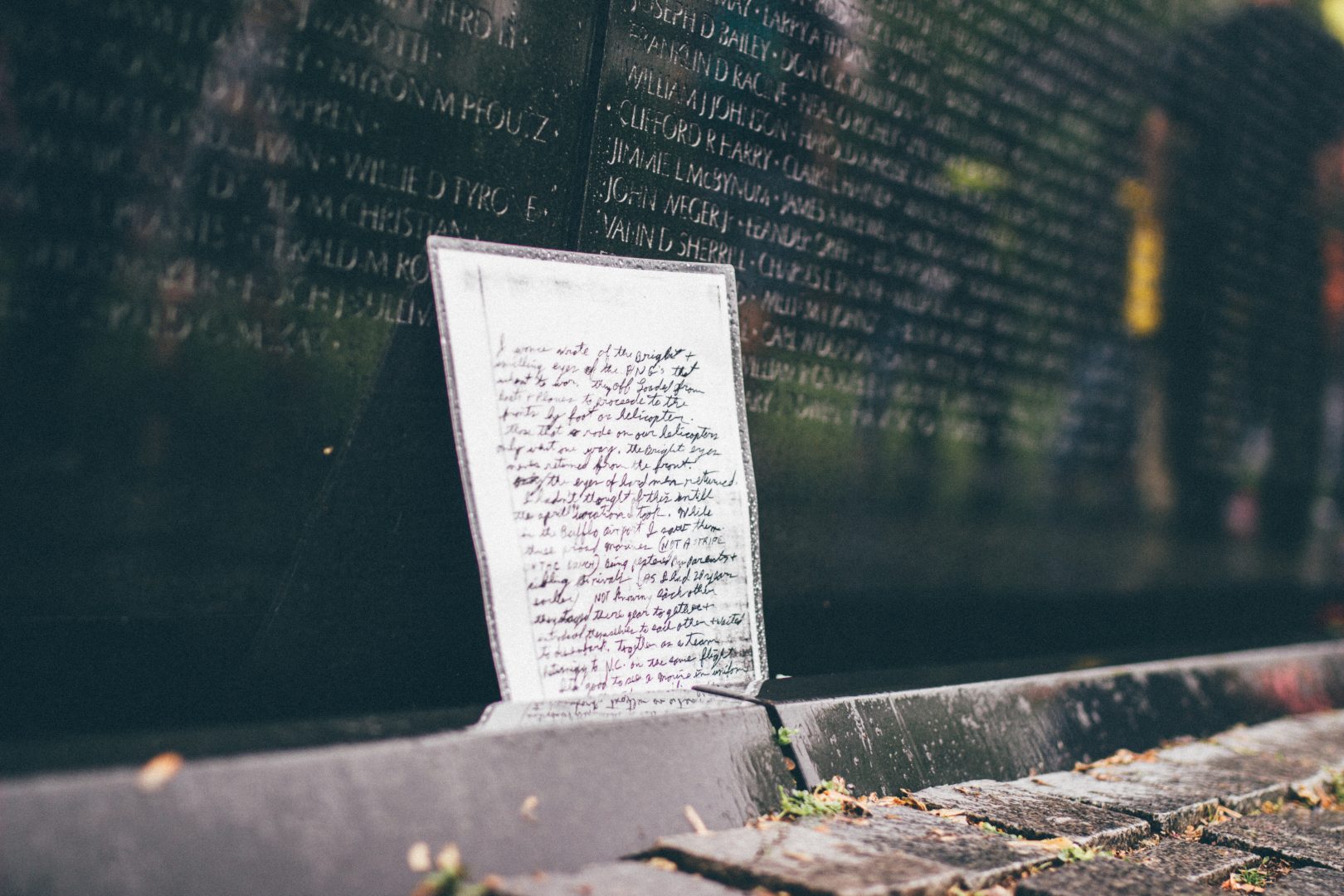

(Washington D.C.) – It’s raining. Hard.

But to a group of men in their 60’s and 70’s, the raindrops, the wind, and gray skies don’t seem to matter. They’re huddled in small groups and chatting in low voices as the walk down a sloping pathway.

They are going to visit some old friends.

Friends who never made it home from the Vietnam War.

Friends whose names are inscribed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington D.C.

The veterans are among 80 who are taking part in Northeastern High School’s Honor Bus trip to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Korean War Memorial, World War Two memorial and Arlington National Cemetery. The York County high school has been honoring military veterans in this way since 2010.

Most vets on the journey are from the Vietnam War. To many of them, the only stop that matters is the “Wall.”

“I’ve got to get down there and see my guys,” one says as he makes his way to the black granite stone. It’s engraved with the names of more than 58,000 men and women who lost their lives in what was once America’s longest war.

The panels of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall are sunken into the ground, each panel taller than the next, peaking at just over 10 feet. Then, it descends again and the final panel is only eight inches high.

“Does this go back to ’61? When the first guy was killed over there?” another vet says. “Where would he be located? Because he was in my outfit.”

The veterans break off into smaller groups to search for names of the friends who never came home. One of the volunteers on the trip approaches a man wearing a Marines baseball cap, black with a red bill, to ask who he was searching for along the panels.

It’s a name Jeff Butch has thought about often, sometimes in his dreams.

“Lonnie Newland,” Butch said…

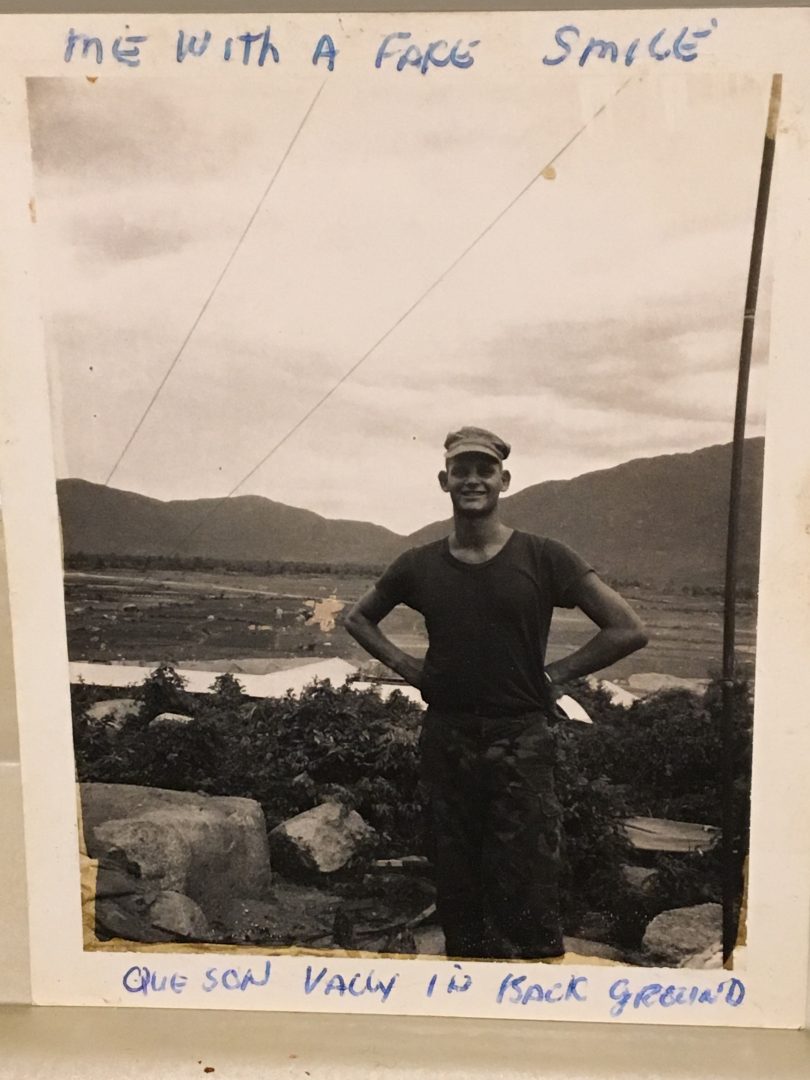

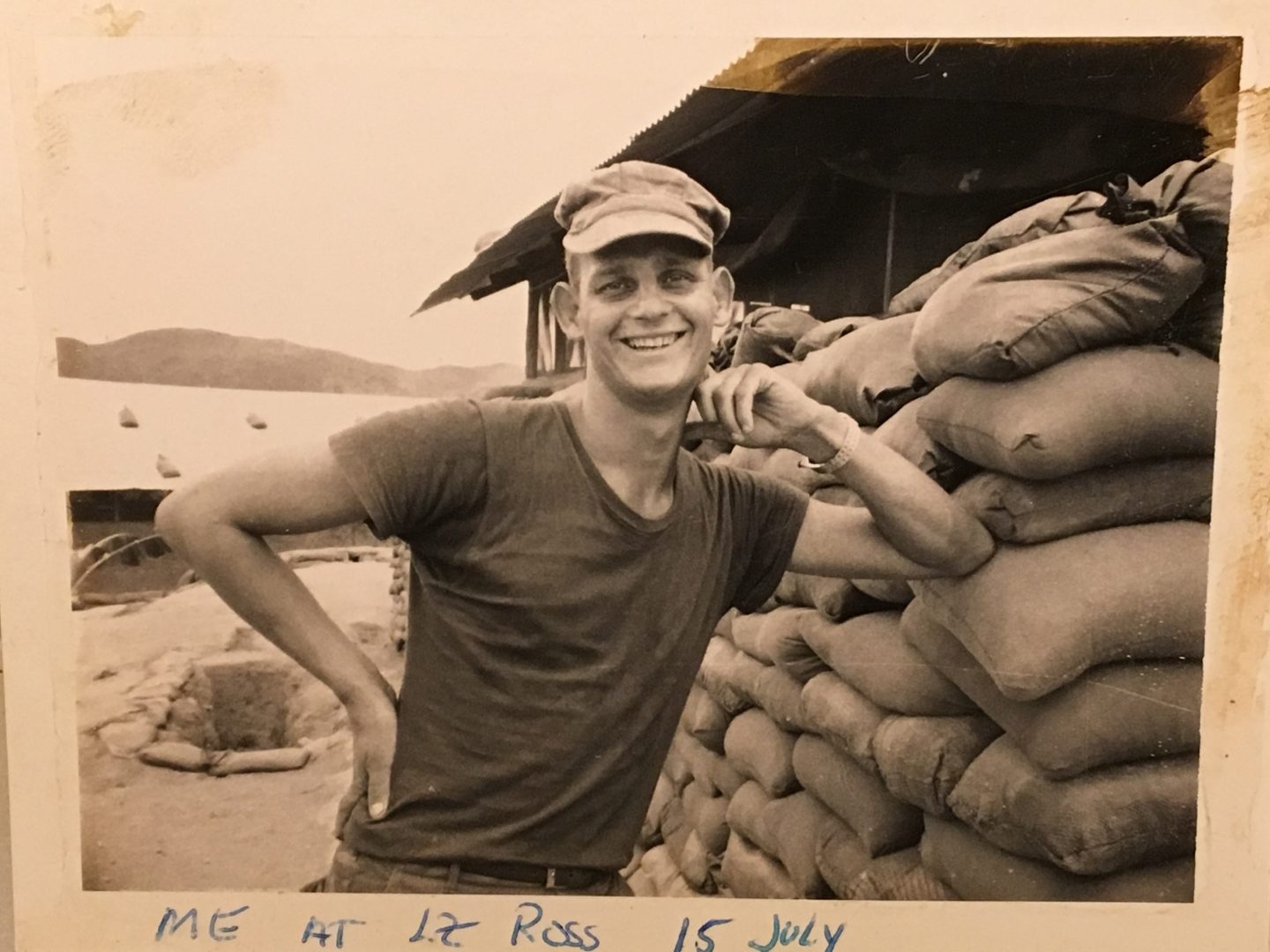

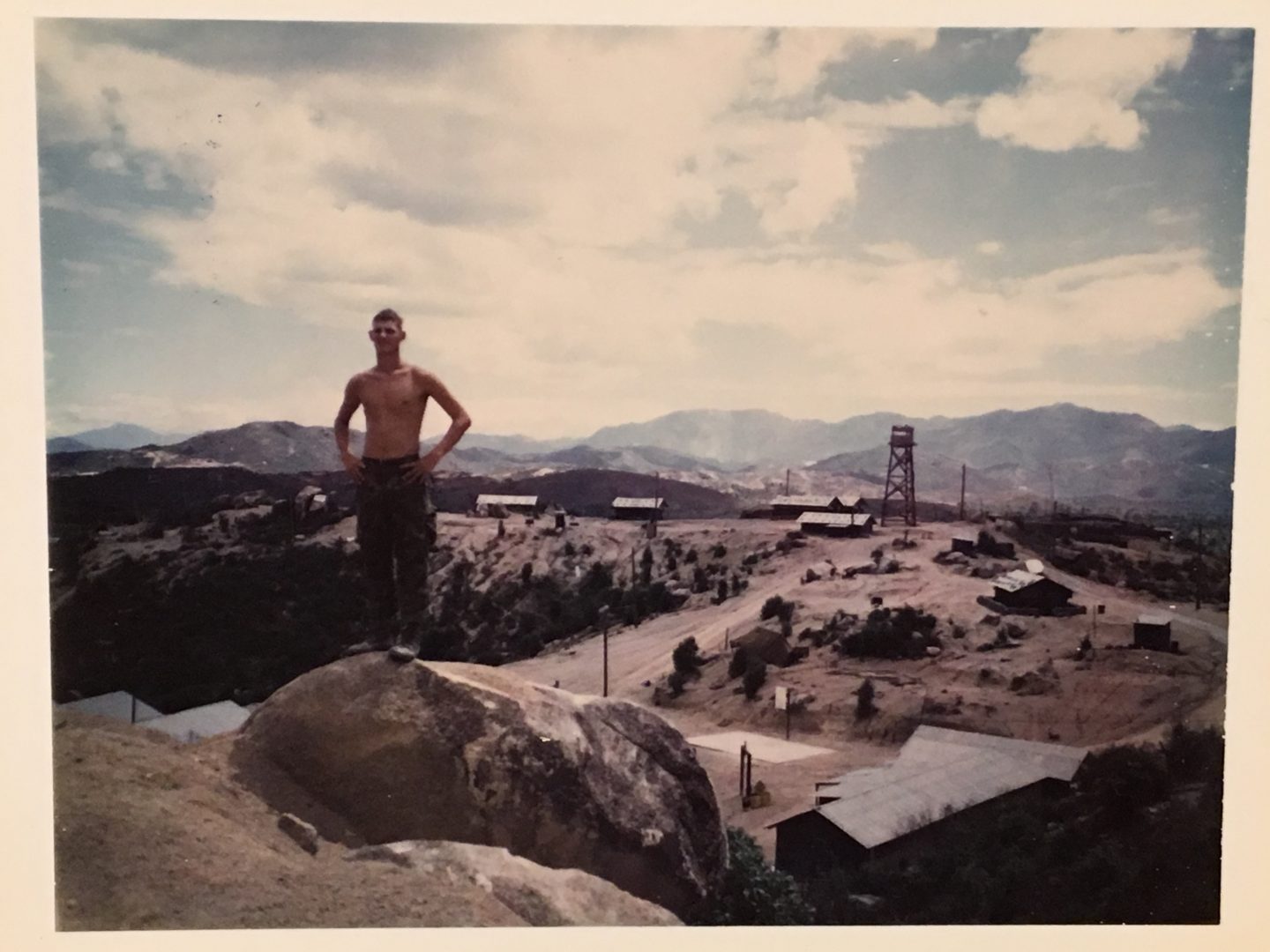

November 1, 1969 is seared in Butch’s memory. That’s when his unit came under mortar fire in the Quay Son Mountains in the province of Quang Nam in South Vietnam.

19-year-old Marine Private First Class Lonnie Pitts Newland of Pinellas Park, Florida, was badly wounded and Butch, a radio operator, was told to stay with him until the medics could get to him.

Butch remembers how Newland fixed his gaze on him.

“So, what do you do? It’s all lit up at night time and he’s there sucking for air. He’s looking at me and he says, ‘I can’t breathe.'” Butch’s eyes widen as rain drips off his purple umbrella. “He just slowly leans back and starts gurgling. Drowns in his own blood. I cried like a baby. What are you going to do? That’s the first time I ever saw death. Nothing can train you for that experience.”

For 40-plus years, Butch felt like he needed to find the young man’s family. He wanted to tell them he was the last person Lonnie saw alive and that he didn’t die alone, thousands of miles from home.

“I know he’s buried in Florida. I got his picture. I have the home address of where he lived, but I don’t know if his parents still live there or if they’re still alive or who’s down there” he says. “I’m trying to contact them. I have to go. It I think it’ll do a lot to bring some closure for me.”

Other veterans are walking up and down the Wall, paying their respects to buddies lost long ago — who are forever young to the men standing before a simple name.

With some help, Butch finds Newland’s name and gets his picture taken in front of it. He stands about 6’2. He has visited here once before. But right now just being in *this* place – in front of all these names – he is visibly affected, both physically and emotionally.

“What a waste of human….” His voice trails off. “Look at all the…We didn’t win. We didn’t lose, but we didn’t win.”

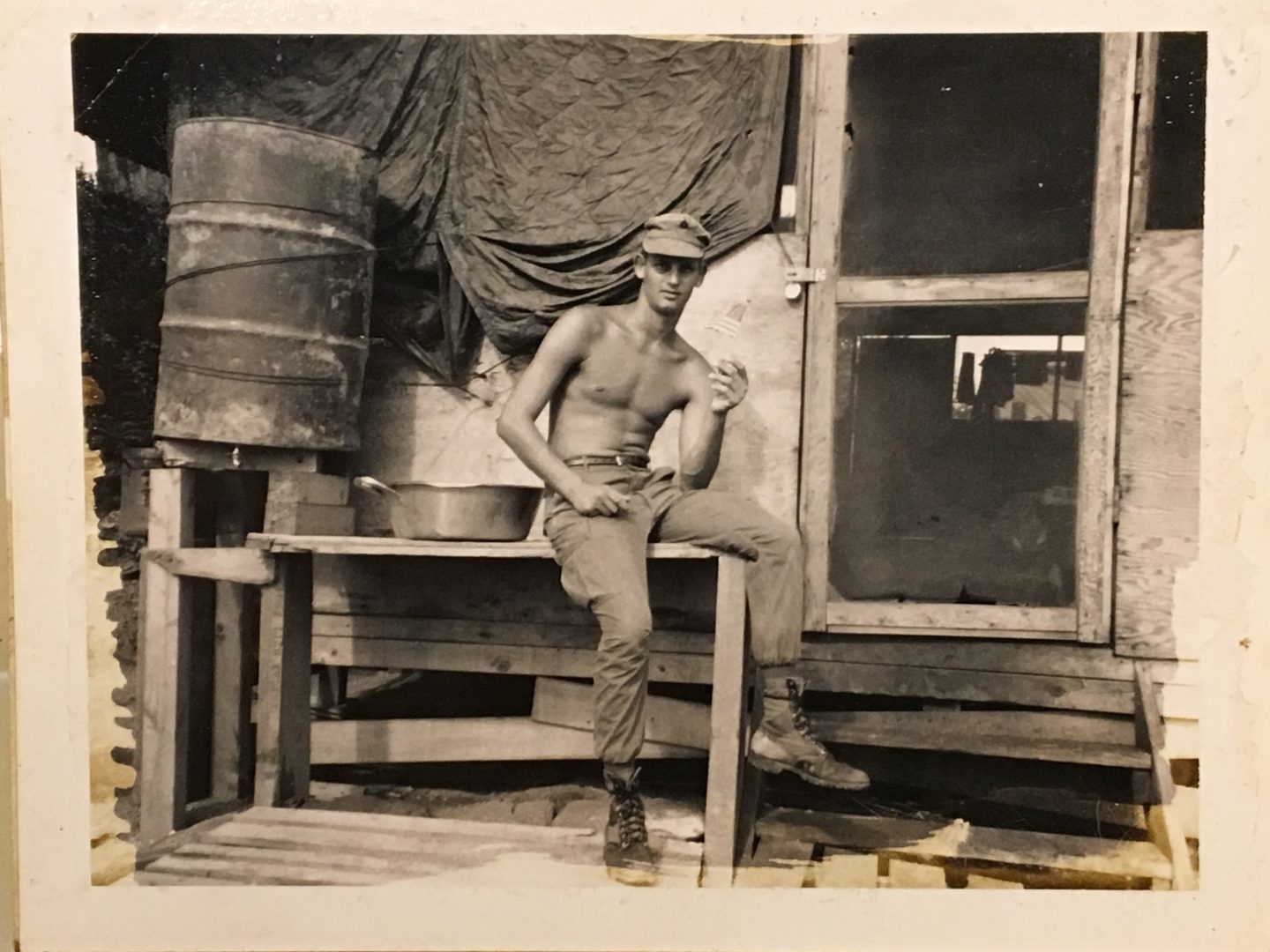

“I sometimes sit and think, ‘Was that just a dream? Did I dream that? Was I really there?” he adds incredulously. “It’s just amazing. It’s hard to think I was there 40-some years ago.”

The healing process for Butch, who served two tours in ‘Nam, has long been a work in progress. As he talks, it’s clear he’s still coming to grips with not only his time in the jungle, but the difficult road he faced when left the Marines at the ripe old age of 20.

“When I came home nobody cared about us. When I went to college, I didn’t even tell anyone I was a Vietnam vet because they would call you names and treat you different,” he says. “That was the hardest thing for me to get over. I don’t know if I’m still 100 percent over it yet. How Americans treated us. They treated you like crap. Like dirt. That hurt. That was a deep scar for me the way the public treated us.”

Butch doesn’t seem to notice the rain has picked up again. He’s in the moment talking with his fellow veterans, connecting in ways only those who saw combat and survived can. He’s also with his brothers and sisters, honoring them the best way he can – by remembering their sacrifice.

“When I look at their names, I see their faces. I see who they are. I kind of smile inside. Someday, I’ll see them again,” he says with a hint of sadness. “Nothing I can do will ever bring them back. It could be me on there. I feel remorse because what did it accomplish?”

Butch, who lives in Lancaster, says he’s become more involved in several veteran’s organizations, so he can be there for former service members who served in Iraq – or Afghanistan, the war that has long surpassed Vietnam as the nation’s longest. He’s proud they’re getting the “Thank you’s” they deserve and — without a hint of bitterness in his voice — notes how far the country has come in treating returning veterans with honor and respect.

But, his story doesn’t end there – standing in the rain, facing the Wall of names.

Remember how he said he wanted to find the family of Lonnie Newland?

Well, several weeks after the honor bus trip, he found a website with Newland’s picture and info about his service. Below it was a post from the late Marine’s sister. So, Butch replied, explaining who he was and how he was with Lonnie in his final moments.

“Maybe three, four weeks afterwards, I get a phone call from Valerie Dean. She left her number. I thought ‘Oh my gosh. I can’t believe it. After all these years, I finally get to talk to somebody from the family,'” he says in a later interview.

He eventually got a hold of Dean and the two talked for more than two hours, shedding tears but also forming a bond.

“His sister was so happy that she could talk to somebody that was with him when he died. That he didn’t die alone,” Butch says. “Being able to talk to her really made me feel good and like she said it was like therapy for both of us.”

Butch plans to call her again and hopes to maybe meet her at Newland’s grave in Florida.

Later this fall, Butch will be taking part in the Reading of the Names of all the men and women killed in Vietnam, part of commemoration of the Wall’s 35th Anniversary.

He’s been assigned a total of 60 names to recite on November 10th.

Among them is Lonnie Newland.